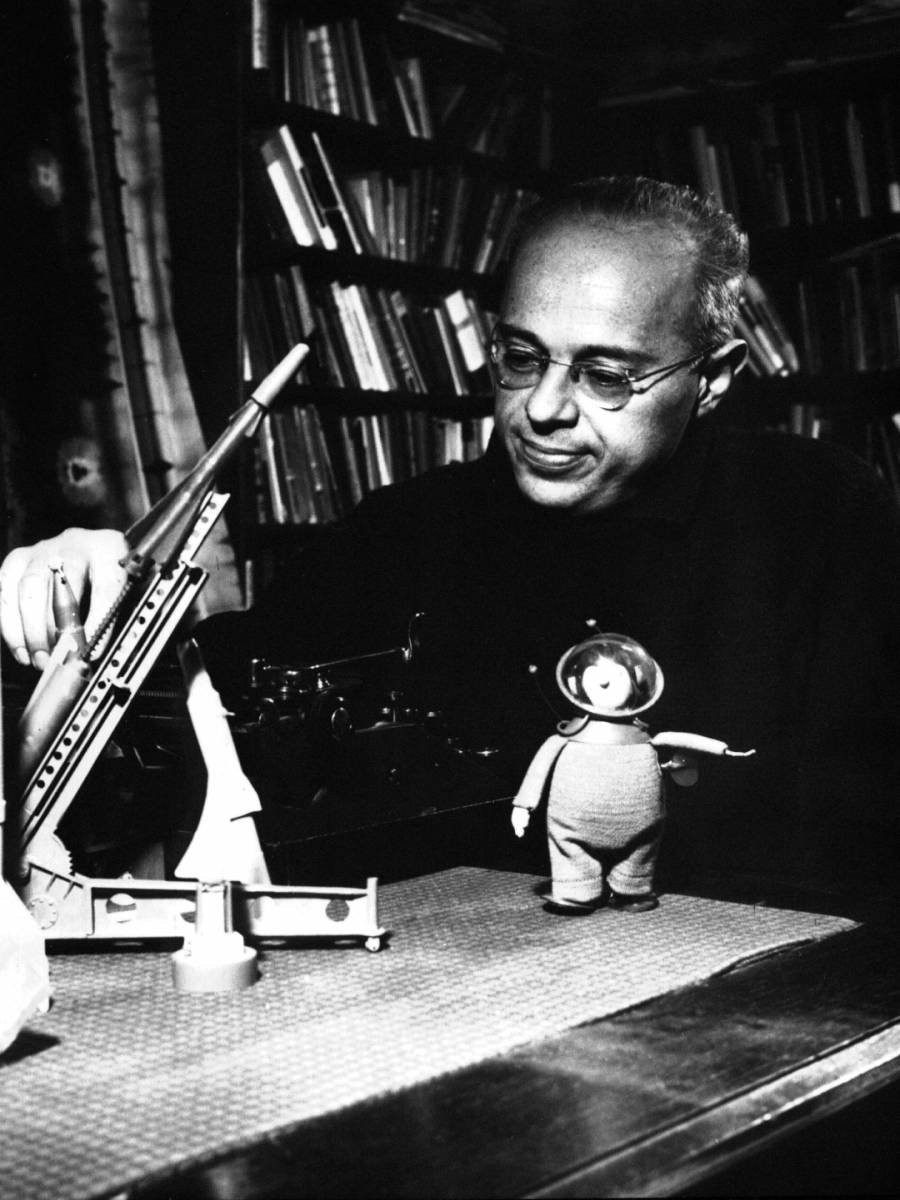

Stanisław Lem was born a hundred years ago this year in Lwów. We talk to Dr. Agnieszka Gajewska, author of a forthcoming biography of the acclaimed science fiction author, about her work on the book.

Karnet: Stanisław Lem talked about his life in interviews, his autobiographical novel Highcastle and numerous letters. Is there much left to be learned about him?

Agnieszka Gajewska: There are plenty of things we still don’t know. While texts such as interviews are generally regarded as autobiographical, in literature there exists a clear distinction between interviews, however extensive, and autobiography. Interviews are limited to questions posed by the interviewer and those the author chose to answer. Additionally, Lem rarely wrote in the first person, so it can be difficult to be certain what he really thought and what he felt regarding certain specific events. Highcastle is an extensive autobiographical essay and a treatise on remembering and forgetting; Lem wrote in the preface that he was describing a single theme from his youth, so it follows that he kept silent on many others. He also produced an extensive body of correspondence, but here he also shied away from personal matters, instead focusing on global issues. He rarely wrote about his thoughts and feelings, even to his closest friends, tending to discuss current events and books he was inspired by. I conducted extensive research for my biography of Stanisław Lem, and all these texts frequently led me astray. In Highcastle especially, Lem omitted many issues or turned them into anecdotes.

His Lwów period remains the least well known, and his family relations are still largely shrouded in mystery. For example, we still don’t know who helped the Lem family hide during the occupation, but they must have had a vast network of contacts, and major funds, in order to survive. I think there is a simple explanation for this gap in our knowledge: it is likely that Lem himself didn’t know who the help came from for security reasons, while shelter was organised by his father Samuel.

I was also interested in Lem’s relationships with women prior to his arrival in Kraków and immediately after expatriation. Little is known about this, although various sources suggest that Lem devoted a great deal of energy to them and that he met with many young women in Lwów and Kraków. I found it important; for example, I wondered what happened to the girl he was involved with and was in hiding with during the occupation. His life features many other mysterious events. But his letters, extensive interviews and other discussions I reached for, or even Highcastle, weren’t texts where he felt free to talk about anything he found embarrassing or he struggled with. Most of the time, his interviewers had no idea about his Jewish roots, so they simply didn’t ask questions which might have proven pertinent. When I read memoirs of other authors writing at the same time – for example Marian Brandys or Lem’s close friend Jan Józef Szczepański – it’s clear that they faced internal struggles; that they were angry with themselves while being aware that one day someone will read what they wrote. I don’t think that Lem was aiming to express his inner struggles the way other authors did, and so we generally don’t know how he was feeling and how he coped with difficult situations.

What was the most difficult element of your work on the biography?

Biography as a genre has close ties with political and social history. When it concerns an author, there is the added element of examining their oeuvre, its origins and impact. I was convinced that I’d find more information about his life in his fiction than his memoirs, but I still had to build a convincing whole from these disperse fragments. I had to take into account tales of pre-war Lwów, explore the topic of expatriation and try to reconstruct the life of a Jewish child growing up during the interwar period; the child becoming a young man surviving the occupation, and later, as an adult, doing his best to distance himself from his Jewish past – which was, of course, not entirely possible. I also studied how the circles of Polish Jews changed after the war. Of course such information can be found in history books, but in order to really understand Lem I also reached for memoirs written by his contemporaries or slightly older authors who shared similar experiences. My work was made considerably more difficult by the fact that Lem tried to erase his Jewish roots and was reluctant to talk about his family – understandable, since any such conversation would have touched upon painful memories of the occupation.

The most difficult task was reconstructing the fates of women surrounding Lem. Their care for him allowed him to work despite various difficulties, including health problems. It has even been difficult to reconstruct the life of his mother, Sabina; she remains one of the biggest mysteries in Lem’s life, even though she lived in Kraków until the 1970s. Joanna Lisek from the Department of Jewish Studies at the University of Wrocław helped me find memoirs and journals of women of a similar age, and their notes helped me reconstruct Sabina’s life in Przemyśl and Lwów. It would have been impossible to learn much about Lem’s wife Barbara if it weren’t for help from the family and local historians. Sadly, women frequently leave little information behind, unless they are very rich, highly educated or are prolific artists, which is why I found it important to include these details in Lem’s biography.

So, we’ve got the Lwów era and women close to Lem… What else stands out in your biography?

One of the main themes is his adventures as an intellectual. I tried to find out how a young man on course to becoming a scientist – he was set on a career in medicine – went on to become a writer, sociologist of science and eventually a philosopher. I wanted to show the different stages of his search for his own niche, which is especially difficult in sociology of science and philosophy. Lem didn’t maintain regular contact with scientific circles, becoming something of a recluse who nevertheless repeatedly attempted to voice his opinions. Sometimes he was listened to, others not, but his dialogue with scientists was hampered by his trouble with maths. This isn’t my suspicion or deduction – Lem had said openly that he struggled to follow some books recommended by scientists precisely because they featured maths problems. He was inspired to become a philosopher by the extraordinary Polish thinker Helena Eilstein. She simply treated him as a philosopher, and that’s likely how Lem came to seeing himself as one.

Another important thing, for me, was whether it was possible for anyone to abandon their Jewish roots if they so chose after the Second World War. While Lem might have initially believed that his ethnicity would be of no relevance in a socialist state and his decision to disassociate himself from being Jewish would be his alone, the anti-Jewish purges of 1968 clearly showed this to be impossible. The terrible year was one of the most difficult in his life and left a powerful mark on all his future choices, including his attitude to involvement in opposition.

My final point concerns Lem and politics, or whether in communist Poland it was possible to simply be a writer while steering clear of conflict with the regime, even to the point of becoming something of a celebrity. On one hand, Lem frequently warned his friends not to get involved, not to stick their necks out, since the authorities could do anything they wanted and writing books was the most important thing there was; on the other, it was no accident that he wrote his most important novels during the Thaw which followed the death of Stalin. His fans describe this time as his golden period. Lem had great hopes in various political events including the Thaw and later the “Solidarity” movement, and while these optimistic visions were soon quashed, he needed them in order to write.

How did Lem want to be perceived as an author?

Lem cared deeply about what was said about him; he was keen to be noted by literary and scientific circles alike. He wanted his writing to be perceived similarly to the work of H.G. Wells or other great authors who have entered the canon of world literature regardless of genre. He disliked being pigeonholed by critics as a science fiction writer since he wanted his books to be discussed more widely. Unfortunately, communist-era censors were especially interested in literary and cultural texts. At times, books would be allowed to go to print but all reviews would be blocked. I haven’t found many rejected reviews of Lem’s writings, but simply knowing that one’s views about a particular book could not be published was dispiriting for potential critics. I’d go as far as saying that expecting genuine debate about books during the communist era was stuff of pure fantasy.

Perhaps unexpectedly, he found the interest he needed in the Soviet Union. During his visits, he was showered with attention and he was introduced to some of the most important scientists working on space flights. When he came back to Kraków, he felt lost and abandoned – not that there’s anything wrong with Kraków, of course… And while Poland also founded a centre for nuclear research, it was significantly less well funded than similar institutions in the USSR, and so Polish scientists weren’t able to admire Lem as much as their Soviet colleagues. In the Soviet Union, Lem was best known as the author of The Astronauts and The Magellanic Cloud; when it became clear that he was losing his optimistic vision of space exploration, interest in translating his books dropped to the extent that he struggled to have them published at all. When they were, they were heavily cut and featured extensive commentary. For example, not all chapters of Solaris were published at first, with the fragments seen as metaphysical simply being edited out.

He also became very popular in Germany, although he wasn’t exactly thrilled with that. Every time he encountered German scientists, who were generally a little older than him, he started by asking what they did during the war. He could never resist reminding them of the past, which would have certainly hampered communication. What he really needed was someone he could engage in healthy debate with. It wasn’t so much about setting himself up as a famous author but about finding partners for discussion.

The publication of his science fiction novels written during his golden era in Russian and English translation brought another wave of fame, and Lem came to realise that he had become more concerned with managing his image than he’d ever intended. He no longer had time for novels because he was preoccupied with replying to various proposals and writing newspaper columns – he was constantly trying to keep up with the demand for futurological visions. Although it was a major drain on his time, he did not employ a secretary until the mid-1990s, since there was no-one he felt he could entrust his affairs to. Lem handled all this himself, and it’s certainly true that the formalities of managing the career of a major author would have been monumental in the era of communist bureaucracy, likely more than a single person could reasonably handle.

Did Lem’s writings feature autobiographical themes, and if so, how?

This is the key question I tried to answer in my previous book The Holocaust and the Stars. The truth was that it was Michael Kandel, the great American scholar and translator of Polish literature into English (including Lem’s works), who noted autobiographical themes in his novels. Due to his own family experience and education, Kandel is highly familiar with the history of this part of Europe, so he understood what Lem’s life was likely to have been like under the occupation. He asked Lem many questions in his letters, which the author answered in detail – which doesn’t mean his answers were unambiguous. Lem changed his mind frequently, and as his trust in Kandel grew, he revealed more about his own life. This mainly concerns Memoirs Found in a Bathtub, which they frequently discussed in their correspondence – first as an account of the Stalinist era and later as a record of Lem’s experiences of the occupation. And so I studied topics and obsessions such as survivor’s guilt and detailed scenes of violence, featured in almost all of Lem’s novels and in certain short stories. At times they are at the forefront, at others they remain in the background; they are nightmarish and, like nightmares, they keep coming back in other writings. It is difficult to be certain whether he included these themes deliberately, although in his letters to Kandel Lem wrote that he spread his own life experience among different characters; that he was the source material for all the problems discussed in his books.

Similar themes appear in Lem’s realist trilogy Time Not Lost and, once again, they are split among several characters. I did not search his books for reconstructions of events; instead I was interested in his accounts of his experiences and emotions, so I sought out scenes exploring fear or inner paralysis. The sociologist and psychologist Barbara Engelking notes that by treating dreams as a source of study of the Holocaust, we can make sense of Lem’s novels which follow the narrative of nightmares. This mainly concerns Memoirs Found in the Bathtub. The structure of a nightmare, bringing back terrifying memories of the past, seems to be the key to understanding what happened in Lwów during the war. During the occupation, concealment or adopting a dual identity were fundamental, and we find these themes in many of Lem’s books: from grotesque visions of the protagonist who encounters his very different self from the previous day to serious considerations of his characters’ personalities. Let’s consider His Master’s Voice: for people who read the book in the 1960s and early 1970s, it was clear that the character of Peter Hogarth represents the book’s author. Lem also wrote to friends, saying that Professor Rappaport’s retrospections reflect his very own’s experiences of the war; I was amazed to find that no-one followed up on this. When you look at Lem’s books from the right perspective, the context reveals many surprises.

Lem’s works abound with dark humour and grotesque and ironic elements. What experiences might have shaped this unique style?

The obvious answer is that they were an attempt to escape the realities of life under communism into literary forms which would express thoughts unacceptable to censors yet understood by readers; forms which would prevent the text from being interfered with. Irony and grotesque were widely used to just this end. I also have the impression that in Lem’s case we are also dealing with “borderland heritage”. The culture of Lwów shaped an unusual combination of “townie” mentality with loftiness, dark humour and irony. It would have been difficult to function in Lwów elites without understanding and reaching for this irony. The multilingual and multicultural city shaped a lifestyle modelled on Vienna through an ironic prism. Lem’s prose resounds with Austrian literary traditions of authors who also reached for grotesque and ironic elements and whom Lem greatly admired. I found a similar sense of humour in Samuel Lem’s poems, but Stanisław honed it to perfection. His neologisms or attempts to combine words from different registers make it clear that he grew up in a world of many languages. He twisted phrases and transcribed Yiddish and Ukrainian words to make them sound amusing and reveal hidden meanings.

This kind of borderlands irony and style is clear throughout his writings, both on the purely linguistic and philosophical levels.

As well as science fiction, Lem also wrote realist novels and many essays. Do you think any of his works are underappreciated?

All fan forums explore all of Lem’s books in great detail. What’s surprised me, however, is that Lem’s screenplays have hardly been analysed, with the exception of Małgorzata Hendrykowska who has studied a few of these texts. Lem decided to become a scriptwriter early, in the 1940s; he put in a lot of energy into the genre and suffered many spectacular setbacks. His main reason for writing screenplays was to earn money, which his science fiction novels weren’t bringing. He tried to get involved with television and cinema – he had close ties with the industry and knew Aleksander Ścibór-Rylski and Andrzej Wajda. Some of his scripts got as far as the production phase, but the majority never saw the light of day. Some of Lem’s scripts have been collected in Przekładaniec [Roly-Poly – trans.].

In terms of non-mainstream publications, I would like to note the essay Biology’s Development Over the Years Leading Up to 2040: A Forecast, written in the 1980s. I am not concerned with whether any of his predictions came true, since this would be difficult to verify by drawing analogies between Lem’s neologisms and real technological innovations. Scientists need a vision of the world with little overlap with reality in order to break through their own mental barriers. In any case, Lem explains that it is not the development of biotechnology that’s difficult per se but the complex problems it generates for lawyers and philosophers. For example, can a gene of a living organism become the property of a corporation? This is something which is now an important subject of discussion by lawyers, corporations and philosophers. I think we rarely see Lem as a scientist reaching for biology rather than physics or maths, and it is an avenue we should explore.

2021 has been announced to be Year of Stanisław Lem. Many of the discussions about the author will be held in the context of the ongoing pandemic. What can we find in Lem’s prose to lift our spirits at this difficult time?

Lem’s novels and stories aren’t exactly a light read, and many critics have written about his misanthropy, admitting that it was rooted in his life’s experience and a sober analysis of the socio-political reality. That said, The Cyberiad and grotesque visions spun in other short stories are filled with humour, fitting in the current situation.

I would also like to note Przekładaniec – a short science fiction comedy film directed by Andrzej Wajda. Lem started writing the script around the time of the first successful organ transplants in humans. He marked and hugely exaggerated fears of people who opposed the breakthrough idea. In his grotesque vision, a transplanted organ gives the recipient the donor’s personality traits, while transplanting organs between men and women erases differences between the sexes. Other themes could just as easily stir debate today, such as transplants from animals into humans. It is a philosophical film which explores human fear of new challenges faced by medicine and the law. At the same time, the film helps us distance ourselves from such fears, since these days organ transplants are widely seen as a standard medical treatment. Better still, many elements of the futuristic vision – such as the stunning costumes designed by Barbara Hoff – have truly stood the test of time. This is a huge achievement for any film made in the 1960s, and especially for a science fiction movie.

Przekładaniec is one of the few successful productions of Lem’s film scripts; popular with the author himself, it can offer us something valuable at the time of the pandemic. First of all, it is available free online! More importantly, it concerned a medical procedure which ignited the public imagination in 1968 and which has since become an almost pedestrian procedure; finally, it shows us how to distance ourselves from lawyers or insurance companies trying to capitalise on the human body. Maybe Przekładaniec, and the Biology's Development… essay mentioned above, can provide can provide a perfect break from the pandemic, allowing us to distance ourselves from myriad conspiracy theories concerning the virus, and helping us consider the rapidly changing global situation.

Interviewed by Anna Mazur

Agnieszka Gajewska works at the Institute of Polish Studies at the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. She is an assistant professor, literary scholar and author of books The Holocaust and the Stars. The Past in Stanisław Lem’s Fiction (2016) and Motto: Feminism (2008). She was the academic editor of an anthology of translations and a co-editor (with Maciej Michalski) of a book on gender studies published in 2020. She heads the Interdisciplinary Centre of Gender and Identity Studies at the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. Her biography of Stanisław Lem will be published later this year.